Photo by Patrick Hendry on Unsplash

No one gives a &*^@# about your DevRel/Community Programs (and what to do about it) #3: Prioritization

How to prevent your desire to help from harming you

In case you're just joining us... we began by discussing a sadly common "organizational apathy" situation found in DevRel/Community work, and we've talked about how to lay solid foundations through organizational alignment and how cross-functional empathy can improve collaboration. What's next?

Sweet! My cross-functional buddies and I are cooking up all KINDS of stuff together!

NOT SO FAST!

If you're like a lot of DevRel / Community folks out there, you ended up in this line of work because you genuinely enjoy helping people. You love writing tutorials to help people learn cool new stuff they can use to save time. You get charged up meeting someone at a conference or meetup who's looking for work, and being the "router" who connects them to someone who's hiring. It totally makes your day hearing product feedback from your peers, and bringing it to the Powers That Be™ so you can get those pain points solved.

And generally speaking, the desire to help others is an amazing trait, and it makes you amazing at your role. Because you actually care, and you will go the extra mile for your community, your customers, and your coworkers.

🚨 But... This trait can also be your downfall, both professionally and personally. 🚨

Because... \cue spooky music**

The road to complete, utter burnout is paved with beautiful, helpful intentions

You see, despite how enthusiastically you want to say "Yes, AND!" to those around you, the fact is:

there's a finite number of hours in a day

there's a finite amount of energy you possess (even when fully loaded up on caffeinated beverages)

there's a finite amount of context-switching your poor brain can handle

and there's no amount of raw enthusiasm that can combat this finite-ness (believe me, I've tried ;))

Conversely, the demands on your / your DevRel team's time are almost infinite and can start to pile up very quickly, especially once you've built out your cross-functional buddy system.

You don't want to drop any balls—people are counting on you!—so you start to take on more and more side-projects, and suddenly you find your main projects that you aligned with your manager on are falling behind, so obviously the only thing to do now is work HARDER and for LONGER hours to try and squeeze everything in, but, well... the requests keep coming (and they don't stop coming) ... and eventually there is only crumbled up bits of burnt out rubble where your enthusiastic, helpful self used to be. 😢

(Ask me how I know. :P)

If you take nothing else from this entire series, here is one thing I would really love for you to remember:

✨ Your enthusiastic, helpful self is an INVALUABLE TREASURE that MUST be protected! And you can't do that without FOCUS, which means saying NO. ✨

Clearly saying "yes" all the time is not the way to go. But being a cantankerous grouch who says "no" all the time doesn't seem like the right thing to do, either.

Luckily, there IS a way forward that your Product buddy might know about.

Friend, let's take a walk yonder to... Product Manager Land™

Apparently DALL-E thinks that Product Manager Land™ requires a great variety of sky-based transport as well as nonsensical words that start with "A."

If you ever do a stint as a Product Manager (esp. of a huge open source project with 2M+ users ;)), one of the things you'll very quickly learn is that everyone has an idea about what should be done to make your product better. Many of these ideas are great. Some of these ideas are crap. Several of these ideas directly conflict with one another in such a way that it's literally impossible to do both. And all of them take time, money, and people to implement.

Something Product Managers intuitively understand:

Every time you say "Yes" to something, you are implicitly saying "No" to a bunch of other things.

But how do you choose what to say "yes" to? Well, here are some less-good ways (which often tend to be how we prioritize in DevRel 😬):

Who is yelling the loudest?

Who has the fanciest title?

What's the quickest/easiest thing we can possibly do?

Which is the most fun/enjoyable thing to work on?

What does my "gut" tell me?

Prioritizing like this might feel like you're being productive, at least for awhile. But without a cohesive strategy behind your actions, you risk spreading yourself too thin, leaving higher-impact things on the table collecting dust, and/or toiling away on things no one else cares about.

What you want to do instead is use data-driven decision making to make your choice, and make your prioritization criteria transparent so that when people raise objections you're able to "show your work" on your thinking.

5 Steps to Guarding Your "Yes"

We're going to use something called a prioritization matrix to help you quickly get a sense of what the highest-impact things are to be working on, and what things ought to be shelved for later. You should still apply common sense to whatever comes out of this exercise, but it can be useful as a starting point.

#1: Create a Backlog of ideas/requests

A "Backlog" is fancy Product-speak for "a big ass honking list." You can use a proper project management tool for this, you can use a spreadsheet for this, it doesn't really matter as long as:

The list aims to be inclusive of ALL requests you could possibly be doing

Anyone at the company can see that list

There's a process so that anyone at the company can add to the list

There's a recurring cadence when this list is reviewed (or "triaged") by you/your team

Why? Well firstly, so you don't forget about these ideas, and they don't scroll off into the ether on Slack back scroll never to be seen again. But the biggest reason is because this allows people making requests to feel heard. Even if your hunch is that their idea is one of the crap ones, you don't even need to have that discussion because, hey... it's on the list! :-)

#2: Identify criteria that influences priority

You want to come up with a small-ish list of factors that when taken together can help you roughly suss out if one idea has more or less merit than another. One great way to do this is to choose criteria that map to each of the goals your team is measured against. If stuck, a good starting point is RICE, which stands for:

Reach: Estimate how many people this idea will affect within a given time period. For example, an event with 2,000 attendees has more "Reach" than an event with 100 attendees.

Impact: Will this idea move the needle on a thing you're measured against? For example, if your team is measured on user signups, does this idea have an angle where you can get people onto your product?

Confidence: How sure are you in your ability to pull this idea off? Is this a copy/pasta of something you've already done before, or is this a totally brand new initiative with lots of unknown unknowns?

Effort: How much work is this going to take to pull off? (Some people use t-shirt sizes for this.) Are we fixing a typo in a tutorial (XXS) or are we creating a demo around a feature still under active development, with collaboration required across multiple timezones and tons of moving parts? (XXL)

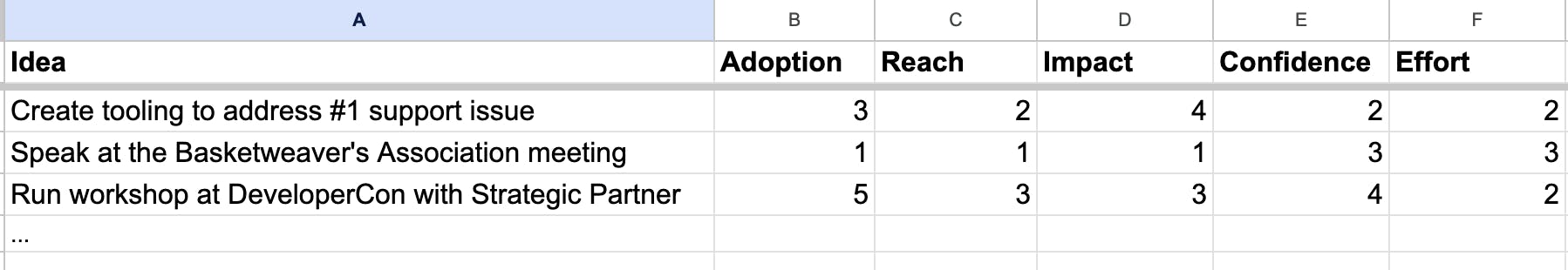

#3: During triage, score each idea against each of your criteria

Pull your ideas list into a spreadsheet if it isn't in one already, and add a column for each of your criteria identified above. Then, talk through each idea, and in each column give it a number.

You can get all fancy here with a Fibonacci sequence and all, but to start simple, you could also just give each a score from 1-5:

For your various criteria columns, 5 is "the most reach-y / impactful / confidence-inspiring / etc. thing we could possibly be doing," 2.5 is kinda "mid," and 1 is "not at all."

Effort though gets scored the inverse — 1 is "OMG HOW EVEN" whereas 5 is "Easy-Peasy."

When finished with this part, you should have something that looks roughly like this:

#4: Sort the backlog by total score

Now add a "score" column to your spreadsheet which multiplies all of the other column values together, and sort the spreadsheet by it. While you might need to play around with scores a bit, generally speaking, the best ideas will float to the top, the other ones less so. Like this:

Any surprises here? Not really:

Running a workshop that gets people hands-on in front of your product at a conference where a large number of your target audience will be in attendance? And doing it in conjunction with a strategic partner so they're promoting it as well? No-brainer. Only other thing you could possibly do after that is turn it into a virtual / on-demand thing to further increase the "Reach" beyond the people at this particular conference.

Creating tooling around the #1 support issue at first seems like a fantastic thing to spend time on (and it also can be super fun!). But here you're mainly impacting existing customers vs. new ones, and the confidence and effort scores suffer a bit because it's a brand new thing you're doing (versus the "rinse and repeat" of a workshop) and it requires cross-team collaboration, debugging, and probably ongoing maintenance as well. So it's not a "no," but it may be a "not yet," or it may be something you set aside for a hackathon or some other sort of dedicated development time.

Whereas, giving a talk in front of the Basketweavers Association? Sorry, but no matter how fiery your passion for basketweaving, if your product targets developers and not basketweavers, and there's no chance anyone in the audience is going to try your product as a result of your talk... this is something probably best kept to individual learning budget (if you can somehow make basketweaving into a work-related connection) or something to pursue in your personal time.

#5: Get Math to say "No" so you don't have to

Now, the next time someone approaches you / your team with a request, show them your prioritized list, and explain the factors that you use to rank them and why. (Ideally this is documented somewhere so you don't need to keep repeating this. ;))

At this point, there's a very high chance that person does some quick mental math and figures out their idea is never going to rank against your criteria, says "never mind," and goes on about their day. (Still capture it in the backlog, though; prioritization factors can change over time as your organization's strategy shifts around.)

But if not, and their idea scores strongly against your criteria, fantastic! Now the discussion needs to shift toward what's moving off the list so the new thing can come on. (And also when, which is hopefully at a future date, so that the team's priorities are not constantly shifting around.)

How much of this list to take on? Enter the "Rule of Threes"

So how much of that nicely sorted list of ideas should you take on? There are entire disciplines around estimating work that teams can reasonably do within a given time period, from hourly estimates, to story points, to planning poker, you name it.

As a Community professional, my specialty is in humans, not in estimation (especially with the ADHD and all 😅). But I'll tell you something I've learned about humans (and it turns out science backs this up):

🧠 Human brains can only focus on about three (3) things at once. 🧠

Even though our brains suck at multitasking, one thing tends to be too few: things can get blocked and you don't want to be just sitting around twiddling your thumbs (in this economy?!). But much more than three, and you're now routinely "swapping to disk" with all the context-switching as your short-term memory fills to bursting, and it takes much longer when you transition to something else.

And even when things are super chill and planned out in advance and clicking along nicely, hey, shit happens. Sometimes the person with the big fancy title does need that thing done by tomorrow. Sometimes a team member gets sick and can't make that event after all, and you now need to hurriedly scramble on last-minute travel logistics. Giving yourself and your team some intentional breathing room allows for this kind of "hair fire" stuff to come up and be handled routinely versus becoming a source of burnout. And if you DO get a randomly chill week, hey, pick up that helpful task for one of your cross-functional buddies, or even sit down and just do some thinking about the future; downtime makes our brains more creative.

So, in summary...

Let's follow our Rule of Threes here. ;) Take a page from the Product world:

Create a discoverable place to capture all of the things your team could possibly be doing

Use math to give you an idea of which of those things are the best things to be working on

Use this to try and keep your week-to-week work down to 3 main areas of focus so you can "flex" when needed

Now that you've got your list of things and your "why," our next instalment, will talk about raising awareness of what your team is doing, which is one of the best insurance policies for your DevRel / Community team. Stay tuned! 😎